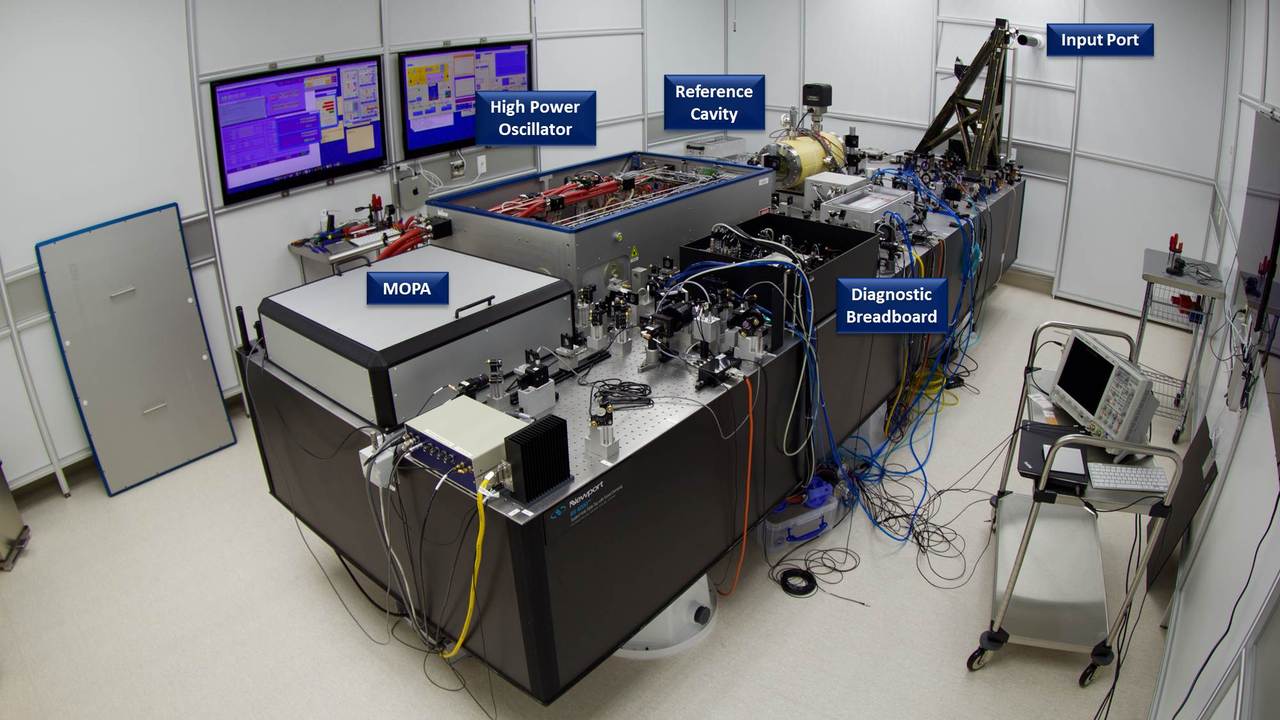

Detailed schematic of LIGO's laser system showing power amplification and frequency stabilization components

LIGO's Laser

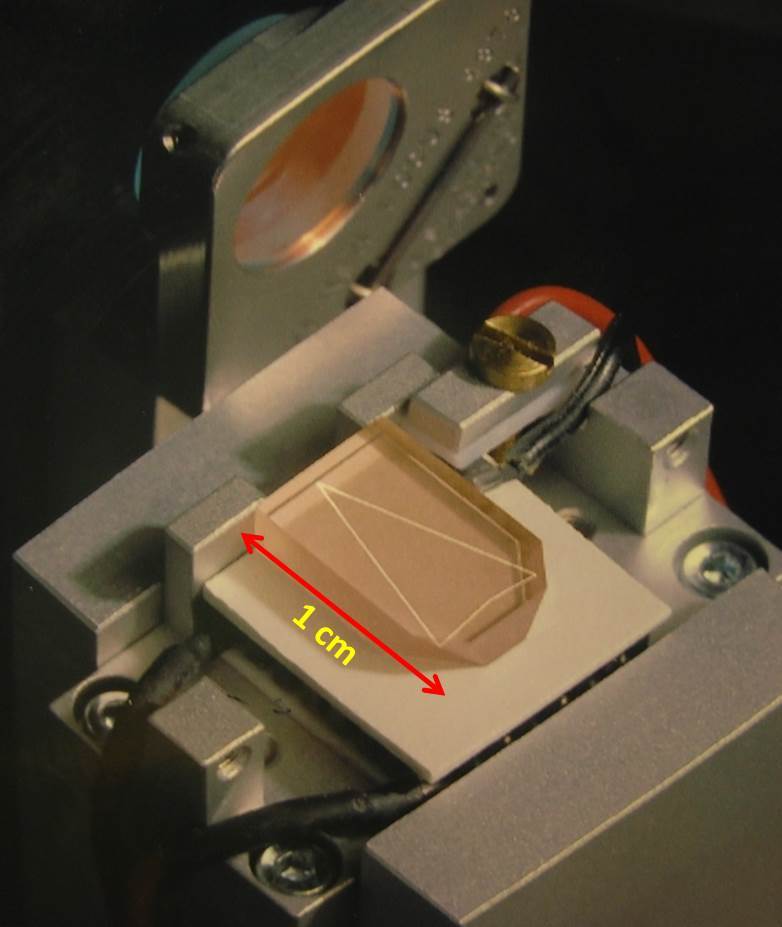

The primary laser beam utilized by the U.S. National Science Foundation Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory's (NSF LIGO) interferometers begins inside a laser diode, which uses electricity to generate a 4-watt 808 nanometer (nm) beam of near-infrared laser light. While laser diodes are the kind of devices that one finds in everyday laser pointers, at 4 watts (W), NSF LIGO's is 800 times more powerful than most off-the-shelf laser pointers. This 4W beam is first sent into a fingernail-sized crystal of man-made garnet, within which it circulates and stimulates the emission of a 2W beam with a wavelength of 1064nm. This crystal lasing device is called a Non-Planar Ring Oscillator (NPRO) and the resulting 2W beam is called a “seed” beam because it will eventually grow into a much more powerful laser.

Non-Planar Ring Oscillator where LIGO's laser begins its journey. (Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab/Peter King)

While 1064nm is the target wavelength for LIGO’s laser, it needs 100 times more power (or 100 times more photons emitted per unit of time) before it can enter the interferometer. To get there, the 2W seed beam undergoes two additional amplification stages that can boost its power up to nearly 200W.

In the multi-faceted first step of amplification, the seed beam passes through a device called a Master Oscillator-Power Amplifier (MOPA). The MOPA contains four thin laser amplifier rods that begin the power-boosting process. These rods, composed of a glass-like material made of neodymium, yttrium, lithium, and fluoride, are about the size of the graphite inside a pencil: just 3mm in diameter and 5cm long.

To amplify the seed beam, the molecules in each rod are first energized by shining a separate 808nm laser into each one. When the seed beam travels through the first rod, the rod's molecules respond by emitting 1064nm photons with the same properties (phase, wavelength) as the incoming seed beam. These new 1064nm photons join those from the seed beam traveling in the same direction, and the power boosting begins (remember, more photons equals more power). This more-powerful beam then travels to the second rod where the amplification process occurs again, and then again in the third, and again in the fourth rod. Like tributaries to a river, at each stage of this amplification process, more and more photons of the same wavelength join the seed beam, gradually increasing its power.

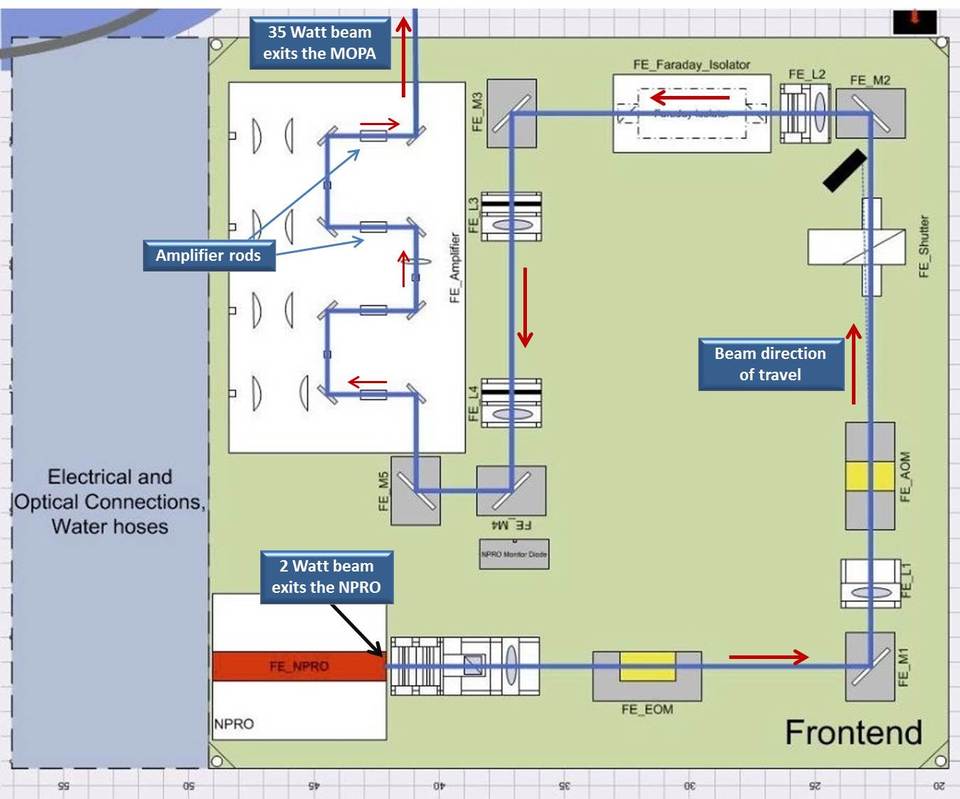

Path of the beam from the MOPA (blue line entering from lower left) through the High Power Oscillator as it is amplified from 35 W to 200 W. (Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

The 2 W beam exits the NPRO (bottom left) and travels via a series of mirrors and lenses through the amplifier rods. Each rod boosts the power a little bit until it reaches 35 W. (Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

By the time the seed beam has passed through all four rods, its power has increased from 2W to about 35W all while maintaining a wavelength of 1064nm. The path that the beam takes from the NPRO through the four rods is shown in the figure at right (click on the image for a larger version).

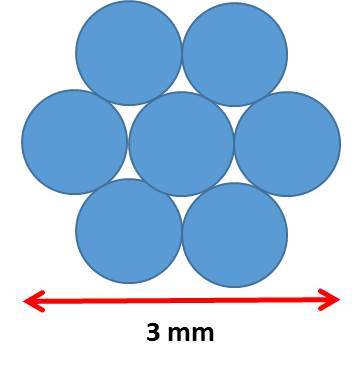

The final stage of power amplification is achieved in another four-rod device called a high power oscillator (HPO). The HPO uses four more amplifier rods, about the same size as the MOPA's rods but made of a different material. As the beam passes through these rods, just like in the MOPA, it gets an additional power boost from laser light funneled through bundles of fiber-optic cables arranged like a flower some 3mm across.

Seven fiber-optic cables deliver 315 W of power to the rods in the HPO, stimulating them to emit more 1064 nm light.

Each fiber carries 45W of laser power, so each bundle delivers 315W (7 fibers x 45W each) into each HPO rod to prime it to emit more and more laser light. By the time the beam exits the HPO it has finally achieved its desired power of 200W. The complexity of this device is revealed in the image below left (click on the image for a larger version).

Frequency and Power Stability

Despite the purity and stability of the initial beam, upon exiting the HPO it is still not stable enough for use. LIGO's laser needs to be 100-million times more stable than it is intrinsically. To achieve this unprecedented level of stability, the beam’s natural frequency variations (caused by its inability to continually radiate a single, discrete color of light) and power fluctuations are mechanically reduced by about a factor of 100-million through a series of feedback mechanisms before the laser is used in the interferometer. This whole process is akin to tuning the world’s most complex piano.

Power fluctuations are also reduced through feedback control loops, which use photodetector data to sense power fluctuations. To learn more about LIGO's feedback and control systems, visit Feedback and Control Systems.

LIGO's laser is generated in its laser room by the numerous devices on the table